Following the recent hype in the media around the importance of early childhood development (ECD), and amidst strong criticism that South Africa is suddenly investing heavily in tertiary education and skills development, officials now have to seriously question the relevance of pouring huge amounts of money into skills development.

This is especially the case since a very large number of these individuals seriously lack the basic fundamentals associated with early learning.

Internationally, educationists agree that a child’s ability to learn is shaped during the first six years of life. Millions of children across South Africa have returned to school in 2016, joined by a whole new intake of young people who started school for the first time.

The sad fact is, says South African experts, that many of these first-graders have already been short-changed as real learning starts even earlier—with well-planned early childhood education.

Achiever tracked down experts Ian Corbishley (Operations Director: The Unlimited Child), Karina Strydom (Co-Founder and Program Developer: BrainBoosters) and Hendrik Marais (Co-Founder: BrainBoosters) to get to the bottom of the story.

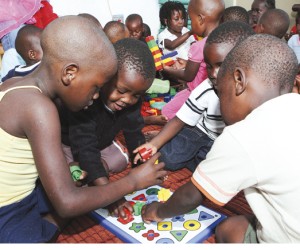

Corbishley says research internationally in recent years has proven categorically that the disadvantage is significant. Children, even from impoverished homes, will have a drastically improved potential if given the correct stimulation during the first 2 000 days of life. The earlier the intervention, the greater the impact. “The process should begin from birth. However, research done in Jamaica has shown that even if the intervention begins at two years, the child’s potential improves significantly. The Unlimited Child’s approach to Early Childhood Education is rooted in informal and structured play which focuses on the social, emotional, physical, intellectual, aesthetic and moral development of each child in our crèches. Activities that cater for Mathematics, Language and Life Skills also enhance the development of fine and gross motor skills. Our programmes are aligned to the National Early Learning Development Standards, the National Curriculum Framework and CAPS.”

Sharing his opinion on how compulsory ECD, as part of the school curriculum, will improve education in South Africa in general, he says the hype around matric results in South Africa is a major factor in denying our seven million pre-school children their constitutional right to quality early learning.

“The media, along with politicians and education bureaucrats, focus exclusively on the National Senior certificate results—but international research proves this is too late and mostly in vain. Each age cohort going through 12 years of schooling loses one million drop-outs before the Grade 12 year. Research by Nobel Prize winning economist Prof JJ Heckman has revealed that the greatest return on education investment is when the investment is predominantly in the first seven years of life.

“In South Africa, we are saying all the right things but, in reality, it is being left to a few NGOs and a handful of businesses to transform early learning. ECD is a multi-faceted sector. It includes nutrition, health, social welfare and HIV/AIDS, among others. All are important, but the Jamaica research has shown that without ECD stimulation programmes in the early years, the child is highly unlikely to reach his/her full potential in adulthood. In South Africa, ECD is given the least attention of all the facets.”

On the same topic, Karina Strydom says it all depends: if the lack of stimulation at home is addressed in an efficient manner, the results at school can be tremendous.

“Many children who are now sitting in class without engaging with the curriculum will start learning. Learners with an early success experience with literacy and numeracy will be more enthusiastic to continue with it. If, however, the ECD curriculum again assumes prior knowledge of concepts and uses applied knowledge to introduce basics, it will probably not make a major difference.

“Academics and teachers underestimate what children can learn in the early ages. By far the best time to learn a second, third or even fourth language is before the age of three! Using the BrainBoosters embedded phonics method to introduce English as a second language in Gr R can have a dramatic impact on literacy and numeracy in our country. It is so easy for children to learn the basic concepts from scratch in English in Gr R, which would give them such a strong learning foundation.”

However, she says this does not mean it should be done instead of mother tongue education, but parallel to it. Transition to English as the language of learning in Gr 4 or 5 will then be smooth and natural because the concepts, skills and vocabulary will be entrenched.

Asked why the lack or nearly absence of early ECD in SA and the impact of it on society has been highlighted only now, Corbishley, a former high school Head Master and Chief Inspector of Schools (Chief Superintendent of Education: Management), says while there are some great organisations doing amazing work, there are also organisations that spend much of their time chasing donor funds, but make little impact on the lives of our children. “In recent years, organisations have emerged that place the children first and partnerships are developing. The Unlimited Child has been doing its bit since 2008 and seeking like-minded partners. The media is also becoming better informed and giving more attention and space to the actual problem.”

But, he says although it is Government’s responsibility to drive processes, the solution is for the public and private sectors to work jointly in partnership. Referring to the introduction of Grade R classes into state schools, Corbishley, who joined The Unlimited to set up a bursary scheme after retiring in 2006, says it has had limited, if any, success, due to lack of training, lack of resources and insufficient suitably qualified teachers.

“At the moment we have failed to get Grade R off the ground in state schools, so we are a long way from implementing a successful pre-Grade R programme.”

Looking at how Government can go about easing this terrible disadvantage, and its role in addressing this problem, Corbishley says Government is between the devil and the deep blue sea.

“Public funds urgently need to be diverted to ECD, especially to early learning. But amidst the likes of #FeesMustFall protests, students are able to attract attention more easily than toddlers. To make matters worse, systemic evaluation of our entire education system place South Africa at the very bottom of the international pile. Our scholars fare very badly compared to scholars in other countries. Quality early learning will improve this dire situation.”

Covering the same topic, Marais says there is no single silver bullet. He feels that with political will and full commitment from the government—a huge chunk of money can be drawn from education budget to improve Grade R and the rest can improve schools. She stressed that no quick fix will work.

His suggestions for role payers to contribute to the alleviation of problems around ECD are:

Use clinics to introduce developmental tools and techniques to new mothers for their babies such as the BB Clinic programme;

Train informal caregivers with a non-academic programme (how to stimulate the minds and teach the basic concepts to children under four);

We must provide them with inexpensive, basic material and incentives to do it, accept the fact that they are probably working from home (maybe a shack) and work with them;

Some of the grant money given to mothers (who might use too much of it for air time, cigarettes and cosmetics) can be paid to caregivers who do more than just keep babies safe and clean;

Teach Gr 9, 10 and 11 learners during Life Skills the importance of stimulating, talking to and reading to their children from birth and before two years of age;

Have parenting skills part of the curriculum—including cognitive development, not just health and safety; and

Encourage the media, such as radio and TV, to discuss the why, who, when and how of early childhood stimulation. Learn from the methods and success of the HIV/Aids program.

Corbishley says, regarding the fact that so few learners pass maths and science is a challenge: “Small children develop language and mathematics skills at a very early age through structured play and a love of reading. Language and cognitive skills start developing in the month before birth and the first year of life is key in establishing the foundation of language and mathematics skills.”

Strydom adds: “There is nothing wrong with the children in this country. The methods and timing that we use to introduce maths and literacy (English as second language) is the problem. If we change the method and blend neuroscience and education, remarkable results can be seen in a short period of time.”

According to Corbishley, the implications for our economy, should we not manage to introduce free ECD programmes to the millions of children whose parents cannot afford to pay for ECD, will be huge, as we have school graduates with poor quality matric passes entering the world of work. Some of our school leavers are unemployable. Unemployment and crime will persist in to the future.

Finally, looking at the role corporate companies can play when it comes to filling the early childhood development gap in order to positively impact South Africa’s future, Corbishley says corporates can make a significant difference by recognising the need to re-direct some of their CSR investment into early learning strategies and interventions.

Presently the focus of investment seems to be on secondary and tertiary education. There needs to be a balance. Families can make a difference by stimulating their own children through appropriate communication and love. Parents must speak to and play with their children from birth. Individuals can volunteer to assist those organisations that are truly making a difference, either through service of financial help.

Marais agrees and says BrainBoosters for instance has launched a parenting intervention programme in 2011 to corporate SA, but companies were not interested in getting their hands dirty.

“Companies would much rather donate money to a charity but don’t expect them to allow their employees to be trained for one hour during working hours on parenting. We provide a parenting training with a monthly theme and a storybox with toys and books. We show parents how to play, talk and interact with their children. In America they now have parenting academies where they train parents how to teach and assist their children.”